B is for Bird

I’m doing folklore and book review posts to reach and please a larger audience. Previous years have shown select interest in both and to minimise blogging throughout the year, I’m focusing my efforts on April.

If you’d rather check out my book review for today, go here.

There are many famous fantastical birds, like the Phoenix, but today’s post is about the ones that people don’t always notice.

Folklore

The Pink Fairy Book by Andrew Lang, [1889]

The Bird ‘Grip’

Translated from the Swedish.

It happened once that a king, who had a great kingdom and three sons, became blind, and no human skill or art could restore to him his sight. At last there came to the palace an old woman, who told him that in the whole world there was only one thing that could give him back his sight, and that was to get the bird Grip; his song would open the King’s eyes.

When the king’s eldest son heard this he offered to bring the bird Grip, which was kept in a cage by a king in another country, and carefully guarded as his greatest treasure. The blind king was greatly rejoiced at his son’s resolve, fitted him out in the best way he could, and let him go. When the prince had ridden some distance he came to an inn, in which there were many guests, all of whom were merry, and drank and sang and played at dice. This joyous life pleased the prince so well that he stayed in the inn, took part in the playing and drinking, and forgot both his blind father and the bird Grip.

Meanwhile the king waited with both hope and anxiety for his son’s return, but as time went on and nothing was heard of him, the second prince asked leave to go in search of his brother, as well as to bring the bird Grip. The king granted his request, and fitted him out in the finest fashion. But when the prince came to the inn and found his brother among his merry companions, he also remained there and forgot both the bird Grip and his blind father.

When the king noticed that neither of his sons returned, although a long time had passed since the second one set out, he was greatly distressed, for not only had he lost all hope of getting back his sight, but he had also lost his two eldest sons. The youngest now came to him, and offered to go in search of his brothers and to bring the bird Grip; he was quite certain that he would succeed in this. The king was unwilling to risk his third son on such an errand, but he begged so long that his father had at last to consent. This prince also was fitted out in the finest manner, like his brothers, and so rode away.

He also turned into the same inn as his brothers, and when these saw him they assailed him with many entreaties to remain with them and share their merry life. But he answered that now, when he had found them, his next task was to get the bird Grip, for which his blind father was longing, and so he had not a single hour to spare with them in the inn. He then said farewell to his brothers, and rode on to find another inn in which to pass the night. When he had ridden a long way, and it began to grow dark, he came to a house which lay deep in the forest. Here he was received in a very friendly manner by the host, who put his horse into the stable, and led the prince himself into the guest-chamber, where he ordered a maid-servant to lay the cloth and set down the supper. It was now dark, and while the girl was laying the cloth and setting down the dishes, and the prince had begun to appease his hunger, he heard the most piteous shrieks and cries from the next room. He sprang up from the table and asked the girl what those cries were, and whether he had fallen into a den of robbers. The girl answered that these shrieks were heard every night, but it was no living being who uttered them; it was a dead man, who life the host had taken because he could not pay for the meals he had had in the inn. The host further refused to bury the dead man, as he had left nothing to pay the expenses of the funeral, and every night he went and scourged the dead body of his victim.

When she had said this she lifted the cover off one of the dishes, and the prince saw that there lay on it a knife and an axe. He understood then that the host meant to ask him by this what kind of death he preferred to die, unless he was willing to ransom his life with his money. He then summoned the host, gave him a large sum for his own life, and paid the dead man’s debt as well, besides paying him for burying the body, which the murderer now promised to attend to.

The prince, however, felt that his life was not safe in this murderer’s den, and asked the maid to help him to escape that night. She replied that the attempt to do so might cost her her own life, as the key of the stable in which the prince’s horse stood lay under the host’s pillow; but, as she herself was a prisoner there, she would help him to escape if he would take her along with him. He promised to do so, and they succeeded in getting away from the inn, and rode on until they came to another far away from it, where the prince got a good place for the girl before proceeding on his journey.

As he now rode all alone through a forest there met him a fox, who greeted him in a friendly fashion, and asked him where he was going, and on what errand he was bent. The prince answered that his errand was too important to be confided to everyone that he met.

‘You are right in that,’ said the fox, ‘for it relates to the bird Grip, which you want to take and bring home to your blind father; I could help you in this, but in that case you must follow my counsel.’

The prince thought that this was a good offer, especially as the fox was ready to go with him and show him the way to the castle, where the bird Grip sat in his cage, and so he promised to obey the fox’s instructions. When they had traversed the forest together they saw the castle at some distance. Then the fox gave the prince three grains of gold, one of which he was to throw into the guard-room, another into the room where the bird Grip sat, and the third into its cage. He could then take the bird, but he must beware of stroking it; otherwise it would go ill with him.

The prince took the grains of gold, and promised to follow the fox’s directions faithfully. When he came to the guard-room of the castle he threw one of the grains in there, and the guards at once fell asleep. The same thing happened with those who kept watch in the room beside the bird Grip, and when he threw the third grain into its cage the bird also fell asleep. When the prince got the beautiful bird into his hand he could not resist the temptation to stroke it, whereupon it awoke and began to scream. At this the whole castle woke up, and the prince was taken prisoner.

As he now sat in his prison, and bitterly lamented that his own disobedience had brought himself into trouble, and deprived his father of the chance of recovering his sight, the fox suddenly stood in front of him. The prince was very pleased to see it again, and received with great meekness all its reproaches, as well as promised to be more obedient in the future, if the fox would only help him out of his fix. The fox said that he had come to assist him, but he could do no more than advise the prince, when he was brought up for trial, to answer ‘yes’ to all the judge’s questions, and everything would go well. The prince faithfully followed his instructions, so that when the judge asked him whether he had meant to steal the bird Grip he said ‘Yes,’ and when the judge asked him if he was a master-thief he again answered ‘Yes.’

When the king heard that he admitted being a master-thief, he said that he would forgive him the attempt to steal the bird if he would go to the next kingdom and carry off the world’s most beautiful princess, and bring her to him. To this also the prince said ‘Yes.’

When he left the castle he met the fox, who went along with him to the next kingdom, and when they came near the castle there, gave him three grains of gold—one to throw into the guard-room, another into the princess’s chamber, and the third into her bed. At the same time he strictly warned him not to kiss the princess. The prince went into the castle, and did with the grains of gold as the fox had told him, so that sleep fell upon everyone there; but when he had taken the princess into his arms he forgot the fox’s warning, at the sight of her beauty, and kissed her. Then both she and all the others in the castle woke; the prince was taken prisoner, and put into a strong dungeon.

Here the fox again came to him and reproached him with his disobedience, but promised to help him out of this trouble also if he would answer ‘yes’ to everything they asked him at his trial. The prince willingly agreed to this, and admitted to the judge that he had meant to steal the princess, and that he was a master-thief.

When the king learned this he said he would forgive his offence if he would go to the next kingdom and steal the horse with the four golden shoes. To this also the prince said ‘Yes.’

When he had gone a little way from the castle he met the fox, and they continued on their journey together. When they reached the end of it the prince for the third time received three grains of gold from the fox, with directions to throw one into the guard-chamber, another into the stable, and the third into the horse’s stall. But the fox told him that above the horse’s stall hung a beautiful golden saddle, which he must not touch, if he did not want to bring himself into new troubles worse than those he had escaped from, for then the fox could help him no longer.

The prince promised to be firm this time. He threw the grains of gold in the proper places, and untied the horse, but with that he caught sight of the golden saddle, and thought that none but it could suit so beautiful a horse, especially as it had golden shoes. But just as he stretched out his hand to take it he received from some invisible being so hard a blow on the arm that it was made quite numb. This recalled to him his promise and his danger, so he led out the horse without looking at the golden saddle again.

The fox was waiting for him outside the castle, and the prince confessed to him that he had very nearly given way to temptation this time as well. ‘I know that,’ said the fox, ‘for it was I who struck you over the arm.’

As they now went on together the prince said that he could not forget the beautiful princess, and asked the fox whether he did not think that she ought to ride home to his father’s palace on this horse with the golden shoes. The fox agreed that this would be excellent; if the prince would now go and carry her off he would give him three grains of gold for that purpose. The prince was quite ready, and promised to keep better command of himself this time, and not kiss her.

He got the grains of gold and entered the castle, where he carried off the princess, set her on the beautiful horse, and held on his way. When they came near to the castle where the bird Grip sat in his cage he again asked the fox for three grains of gold. These he got, and with them he was successful in carrying off the bird.

He was now full of joy, for his blind father would now recover his sight, while he himself owned the world’s most beautiful princess and the horse with the golden shoes.

The prince and princess travelled on together with mirth and happiness, and the fox followed them until they came to the forest where the prince first met with him.

‘Here our ways part,’ said the fox. ‘You have now got all that your heart desired, and you will have a prosperous journey to your father’s palace if only you do not ransom anyone’s life with money.’

The prince thanked the fox for all his help, promised to give heed to his warning, said farewell to him, and rode on, with the princess by his side and the bird Grip on his wrist.

They soon arrived at the inn where the two eldest brothers had stayed, forgetting their errand. But now no merry song or noise of mirth was heard from it. When the prince came nearer he saw two gallows erected, and when he entered the inn along with the princess he saw that all the rooms were hung with black, and that everything inside foreboded sorrow and death. He asked the reason of this, and was told that two princes were to be hanged that day for debt; they had spent all their money in feasting and playing, and were now deeply in debt to the host, and as no one could be found to ransom their lives they were about to be hanged according to the law.

The prince knew that it was his two brothers who had thus forfeited their lives and it cut him to the heart to think that two princes should suffer such a shameful death; and, as he had sufficient money with him, he paid their debts, and so ransomed their lives.

At first the brothers were grateful for their liberty, but when they saw the youngest brother’s treasures they became jealous of his good fortune, and planned how to bring him to destruction, and then take the bird Grip, the princess, and the horse with the golden shoes, and convey them to their blind father. After they had agreed on how to carry out their treachery they enticed the prince to a den of lions and threw him down among them. Then they set the princess on horseback, took the bird Grip, and rode homeward. The princess wept bitterly, but they told her that it would cost her her life if she did not say that the two brothers had won all the treasures.

When they arrived at their father’s palace there was great rejoicing, and everyone praised the two princes for their courage and bravery.

When the king inquired after the youngest brother they answered that he had led such a life in the inn that he had been hanged for debt. The king sorrowed bitterly over this, because the youngest prince was his dearest son, and the joy over the treasures soon died away, for the bird Grip would not sing so that the king might recover his sight, the princess wept night and day, and no one dared to venture so close to the horse as to have a look at his golden shoes.

Now when the youngest prince was thrown down into the lions’ den he found the fox sitting there, and the lions, instead of tearing him to pieces, showed him the greatest friendliness. Nor was the fox angry with him for having forgot his last warning. He only said that sons who could so forget their old father and disgrace their royal birth as those had done would not hesitate to betray their brother either. Then he took the prince up out of the lion’s den and gave him directions what to do now so as to come by his rights again.

The prince thanked the fox with all his heart for his true friendship, but the fox answered that if he had been of any use to him he would now for his own part ask a service of him. The prince replied that he would do him any service that was in his power.

‘I have only one thing to ask of you,’ said the fox, ‘and that is, that you should cut off my head with your sword.’

The prince was astonished, and said that he could not bring himself to cut the had off his truest friend, and to this he stuck in spite of all the fox’s declarations that it was the greatest service he could do him. At this the fox became very sorrowful, and declared that the prince’s refusal to grant his request now compelled him to do a deed which he was very unwilling to do—if the prince would not cut off his head, then he must kill the prince himself. Then at last the prince drew his good sword and cut off the fox’s head, and the next moment a youth stood before him.

‘Thanks,’ said he, ‘for this service, which has freed me from a spell that not even death itself could loosen. I am the dead man who lay unburied in the robber’s inn, where you ransomed me and gave me honourable burial, and therefore I have helped you in your journey.’

With this they parted and the prince, disguising himself as a horse-shoer, went up to his father’s palace and offered his services there.

The king’s men told him that a horse-shoer was indeed wanted at the palace, but he must be one who could lift up the feet of the horse with the golden shoes, and such a one they had not yet been able to find. The prince asked to see the horse, and as soon as he entered the stable the steed began to neigh in a friendly fashion, and stood as quiet and still as a lamb while the prince lifted up his hoofs, one after the other, and showed the king’s men the famous golden shoes.

After this the king’s men began to talk about the bird Grip, and how strange it was that he would not sing, however well he was attended to. The horse-shoer then said that he knew the bird very well; he had seen it when it sat in its cage in another king’s palace, and if it did not sing now it must be because it did not have all that it wanted. He himself knew so much about the bird’s ways that if he only got to see it he could tell at once what it lacked.

The king’s men now took counsel whether they ought to take the stranger in before the king, for in his chamber sat the bird Grip along with the weeping princess. It was decided to risk doing so, and the horse-shoer was led into the king’s chamber, where he had no sooner called the bird by its name than it began to sing and the princess to smile. Then the darkness cleared away from the king’s eyes, and the more the bird sang the more clearly did he see, till at last in the strange horse-shoer he recognised his youngest son. Then the princess told the king how treacherously his eldest sons had acted, and he had them banished from his kingdom; but the youngest prince married the princess, and got the horse with the golden shoes and half the kingdom from his father, who kept for himself so long as he lived the bird Grip, which now sang with all its heart to the king and all his court.

Popular Tales of the West Highlands by J. F. Campbell Volume I [1890]

Birds are very often referred to as soothsayers–in No. 39 especially; the man catches a bird and says it is a diviner, and a gentleman buys it as such. It was a bird of prey, for it lit on a hide, and birds of prey are continually appearing as bringing aid to men, such as the raven, the hoodie, and the falcon. The little birds especially are frequently mentioned. I should therefore gather from the stories that the ancient Celts drew augury from birds as other nations did, and as it is asserted by historians that the Gauls really did. I should be inclined to think that they possessed the domestic fowl before they became acquainted with the country of the wild grouse, and that the cock may have been sacred, for he is a foe and a terror to uncanny beings, and the hero of many a story; while the grouse and similar birds peculiar to this country are barely mentioned.

There is a gigantic water bird, called the Boobrie, which is supposed to inhabit the fresh water and sea lochs of Argyllshire. I have heard of him nowhere else; but I have heard of him from several people.

He is ravenous and gigantic, gobbles up sheep and cows, has webbed feet, a very loud hoarse voice, and is somewhat like a cormorant. He is reported to have terrified a minister out of his propriety, and it is therefore to be assumed that he is of the powers of evil. And there are a vast number of other fancied inhabitants of earth, air, and water, enough to form a volume of supernatural history, and all or any of these may have figured in Celtic mythology; for it is hard to suppose that men living at opposite ends of Scotland, and peasants in the Isle of Man, should invent the same fancies unless their ideas had some common foundation.

Basque Legends by Wentworth Webster [1879]

THE WHITE BLACKBIRD.

LIKE many others in the world, there was a king who had three sons. This king was blind, and he had heard one day that there was a king who had a white blackbird, which gave sight to the blind. When his eldest son heard that, he. said to his father that he would go and fetch this white blackbird as quickly as possible.

The father said to him, “I prefer to remain blind rather than to separate myself from you, my child.”

The son says to him, “Have no fear for me; with a horse laden with money I will find it and bring it to you.”

He goes off then, far, far, far away. When night came he stopped. One evening he stopped at an inn where there were three very beautiful young ladies. They said to him. that they must have a game of cards together. He refuses; but after many prayers and much pressing they begin. He loses all his money, his horse, and also has a large debt against his word of honour. In this country it was the custom for persons who did not pay their debts to be put in prison, and if they did not pay after a given time they were put to death, and then afterwards they were left at the church doors until someone should pay their debts. 1 They therefore put this king’s son in prison.

The second son, seeing that his brother did not return, said to his father that he wished to go off, (and asked him) to give him a horse and plenty of money, and that certainly he would not lose his time. He sets off, and, as was fated to occur, he goes to the inn where his brother had been ruined. After supper these young ladies say to him:

“You must have a game of cards with us.”

He refuses, but these young ladies cajole him so well, and turn him round their fingers, that he ends by consenting. They begin then, and he also loses all his money, his horse, and makes a great many debts besides. They put him in prison like his brother.

After some time the king and his youngest son are in deep grief because some misfortune must have happened to them, and the youngest asks leave to set out.

“I assure you that I will do something. Have no anxiety on my account.”

This poor father lets him go off, but not with a good will. He kept saying to him that he would prefer to be always blind; but the son would set off. His father gives him a beautiful horse, and as much gold as his horse could carry, and his crown. He goes off far, far, far away. They rested every night, and he happened, like his brothers, to go to the same inn. After supper these young ladies say to him:

“It is the custom for everyone to play at cards here.”

He says that it is not for him, and that he will not play. The young ladies beg him ever so much, but they do not succeed with this one in any fashion whatever. They cannot make him play. The next morning he gets up early, takes his horse, and goes off. He sees that they are leading two men to death. He asks what they have done, and recognises his two brothers. They tell him that they have not paid their debts within the appointed time, and that they must be put to death. But he pays the debts of both, and goes on. Passing before the church he sees that they are doing something. He asks what it is. They tell him that it is a man who has left some debts, and that until someone pays them he will be left there still. He pays the debts again.

He goes on his journey, and arrives at last at the king’s house where the blackbird was. Our king’s son asks if they have not a white blackbird which restores sight. They tell him, “Yes.” Our young gentleman relates how that his father is blind, and that he has come such a long way to fetch it to him.

The king says to him, “I will give you this white blackbird, when you shall have brought me from the house of such a king a young lady who is there.”

Our young man goes off far, far, far away. When he is near the king’s house a fox 1 comes out and says to him,

“Where are you going to?”

He answers, “I want a young lady from the king’s house.”

He gives his horse to the fox to take care of, and the fox says to him:

“You will go to such a room; there will be the young lady whom you need. You will not recognise her because she has old clothes on, but there are beautiful dresses hanging up in the room. You will make her put on one of those. As soon as she shall have it on, she will begin to sing and will wake up everybody in the house.”

He goes inside as the fox had told him. He finds the young lady. He makes her put on the beautiful dresses, and as soon as she has them on she begins to sing and to carol. Everyone rushes into this young lady’s room. The king in a rage wished to put him in prison, but the king’s son shows his crown, and tells how such a king sent him to fetch this young lady, and when once he has brought her he promises him the white blackbird to open his father’s eyes.

The king then says to him, “You must go to the house of such a king, and you must bring me from there a white horse, which is very, very beautiful.”

Our young man sets out, and goes on, and on, and on. As he comes near the house of the king, the fox appears to him and says to him:

“The horse which you want is in such a place, but he has a bad saddle on. You will put on him that which is hanging up, and which is handsome and brilliant. As soon as he shall have it on he will begin to neigh, so much as not to be able to stop. 1 All the king’s people will come to see what is happening, but with your crown you will always get off scot free.”

He goes off as the fox had said to him. He finds the horse with the bad saddle, and puts on him the fine one, and then the horse begins to neigh and cannot stop himself. People arrive, and they wish to put the young man in prison, but he shows them his crown, and relates what king had sent him to fetch this horse in order to get a young lady. They give him the horse, and he sets off.

He comes to the house of the king where the young lady was. He shows his horse with its beautiful saddle, and asks the king if he would not like to see the young lady take a few turns on this beautiful horse in the courtyard. The king says, “Yes.” As the young lady was very handsomely dressed when she mounted the horse, our young man gives the horse a little touch with his stick, and they set off like the lightning. The king’s son follows them, and they go both together to the king who had the white blackbird. They ask him for the blackbird, and the bird goes of itself on to the knees of the young lady, who was still on horseback. The king’s son gives him a blow, and they set off at full gallop; he also escapes in order to rejoin them. They journey a long, long time, and approach their city.

His brothers had heard the news how that their brother was coming with the white blackbird. These two brothers had come back at last to their father’s house, and they had told their father a hundred falsehoods; how that robbers had taken away their money, and many things like that. The two brothers plotted together, and said that they must hinder their brother from reaching the house, and that they must rob him of the blackbird.

They keep expecting him always. One day they saw him coming, and they say that they must throw him into a cistern, and they do as they say. They take the blackbird and throw him and the lady into the water, and leave the horse outside. The fox comes to them on the brink of the cistern, and says to them:

“I will leap in there; you will take hold of my tail one by one, and I will save you.”

The two wicked brothers had taken the blackbird, but he escaped from them as they entered the house, and went on to the white horse. Judge of the joy of the youngest brother when he sees that nothing is wanting to them! They go to the king. As soon as they enter the young lady begins to carol and to sing, the bird too, and the horse to neigh. The blackbird of its own accord goes on to the king’s knees, and there by its songs restored him to sight. The son relates to his father what labours he underwent until he had found these three things, and he told him how he had saved two men condemned to death by paying their debts, and that they were his two brothers; that he had also paid the debts of a dead man, and that his soul (the fox was his soul) had saved him from the cistern into which his brothers had thrown him.

Think of the joy of the father, and his sorrow at the same time, when he saw how wisely this young son had always behaved, and how wicked his two brothers had been. As he had well earned her, he was married to the young lady whom he had brought away with him, and they lived happily and joyfully. The father sent the two brothers into the desert to do penance. If they had lived well, they would have died well.

Folk-lore of Shakespeare, by T.F. Thiselton Dyer, [1883]

CHAPTER VI. BIRDS.

Barnacle-Goose.—There was a curious notion, very prevalent in former times, that this bird (Anser bernicla) was generated from the barnacle (Leilas anatifera), a shell-fish, growing on a flexible stem, and adhering to loose timber, bottoms of ships, &c., a metamorphosis to which Shakspeare alludes in the “Tempest” (iv. i), where he makes Caliban say—

“We shall lose our time, And all be turn’d to barnacles.”

This vulgar error, no doubt, originated in mistaking the fleshy peduncle of the shell-fish for the neck of a goose, the shell for its head, and the tentacula for a tuft of feathers. These shell-fish, therefore, bearing, as seen out of the water, a resemblance to the goose’s neck, were ignorantly, and without investigation, confounded with geese themselves. In France, the barnacle-goose may be eaten on fast days, by virtue of this old belief in its fishy origin. 1 Like other fictions this one had its variations, for sometimes the barnacles were supposed to grow on trees, and thence to drop into the sea, and become geese, as in Drayton’s account of Furness, (Polyolb. 1622, Song 27, p. 1190). As early as the 12th century this idea was promulgated by Giraldus Cambrensis in his “Topographia Hiberniæ.” Gerarde, who in the year 1597 published his “Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes,” narrates the following:—”There are found in the north parts of Scotland, and the isles adjacent called Orcades, certain trees, whereon do grow certain shell-fishes, of a white colour, tending to russet, wherein are contained little living creatures; which shells in time of maturity do open, and out of them grow those little living things, which, falling into the water, do become fowls, whom we call barnacles, in the north of England brant geese, and in Lancashire tree geese; but the others that do fall upon the land perish, and do come to nothing.

Owl.—The dread attached to this unfortunate bird is frequently spoken of by Shakespeare, who has alluded to several of the superstitions associated with it. Singer in his Notes on this passage (ii. p. 28) says—”It has been asked, how should Shakespeare know that screech-owls were considered by the Romans as witches?” Do these cavillers think that Shakespeare never looked into a book? Take an extract from the Cambridge Latin Dictionary (1594, 8vo), probably the very book he used: “Strix, a scritche owle; an unluckie kind of bird (as they of olde time said) which sucked out the blood of infants lying in their cradles; a witch, that changeth the favour of children; an hagge or fairie.” So in the “London Prodigal,” a comedy, 1605:—”Soul, I think I am sure crossed or witch’d with an owl.” 2 In the “Tempest” (v. 1), Shakespeare introduces Ariel as saying—

“Where the bee sucks, there suck I,

In a cowslip’s bell I lie,

There I couch when owls do cry.”

Ariel, who sucks honey for luxury in the cowslip’s bell, retreats thither for quiet when owls are abroad and screeching.

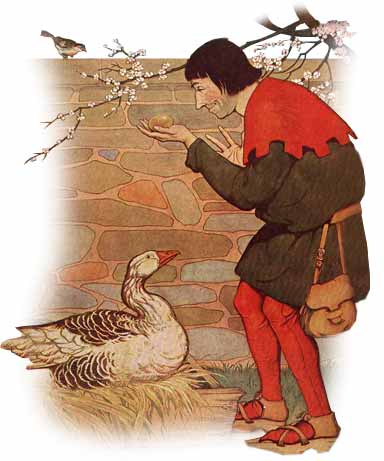

The Goose & the Golden Egg, Aesop’s Fables

There was once a Countryman who possessed the most wonderful Goose you can imagine, for every day when he visited the nest, the Goose had laid a beautiful, glittering, golden egg.

The Countryman took the eggs to market and soon began to get rich. But it was not long before he grew impatient with the Goose because she gave him only a single golden egg a day. He was not getting rich fast enough.

Then one day, after he had finished counting his money, the idea came to him that he could get all the golden eggs at once by killing the Goose and cutting it open. But when the deed was done, not a single golden egg did he find, and his precious Goose was dead.

Those who have plenty want more and so lose all they have.

Moral of the story…

Encyclopedia of Fairies in World Folklore and Mythology by Theresa Bane

Birds of Rhiannon

The birds of Rhiannon were fairy animals of British folklore; typically their number was given as three. These birds are wonderful musicians with the ability to sing the dead back to life. According to the “Mabinogi of Branwen, Daughter of Llyr” a warrior came upon the birds and was so enchanted by their song he stopped and listened to them sing for 80 consecutive years; there are many versions of this story.

Boobrie

The boobrie is a fairy-bird from the Scottish Highlands haunting lakes and salt-water wells; it is said to fly through the water. Its favourite food is cattle and sheep and will attack any ship carrying them. The boobrie mimics the sound of a calf or lamb in the hopes of luring an adult animal to the side of the ship; if successful, it will use its long talons to grab the animal and drag it underwater and drown it. When cows and sheep are not available, it eats otters.

The boobrie has the ability to shape-shift into a horse; in this form it can run across the surface of the water and when it does so, its hoof beats sound as if it were running over solid ground. It also shape-shifts into the form of a large insect with tentacles and feeds off horse blood. The foot-print of the boobrie looks like the imprint of an antler.

Nemglan

Nemglan was the Irish fairy king of birds. Appearing on only one myth, Nemglan appeared to the heroine Mess Buachalla in the form of a bird and seduced her. Their son, Conaire went on to become a king of Tara; he was forbidden to ever harm a bird because of his origins. Before Conaire is crowned king, his father, Nemglan appears to him and explains to his son the secrets of success.

White Merle

In ancient Basque lore the white merle is a fairy animal, a bird whose singing could restore sight to the blind.

Hyter Sprite

Variations: Hyster

In East Anglia and Lincolnshire, England, hyster sprites are a type of fairy which shape-shift into sand martins, a species of regional bird. Naturally sandy-brown in colour with bright green eyes hyster sprites are known together in groups and fly dangerously close to humans.

*Read more in the book.

A Wizard’s Bestiary by Oberon Zell Ravenheart and Ash “LeopardDancer” DeKirk

Achiyalabopa

This celestial bird hails from Pueblo Indian myth. Its rainbow-colored feathers are said to be sharp as knives. It is reminiscent of the Stymphalian Birds that Heracles killed for his sixth Labor.

Adar Llwch Gwin

These bird-like creatures of Welsh Arthurian myth could understand human speech. They were commanded by Drudwas, and were used for magickal combat as well as for protection. They were so loyal to their master that they killed him after he ordered that they slay the first knight to appear on a field of battle. His opponents were delayed, making Drudwas the first to arrive.

Alicanto

A luminous bird of Chile that feeds on silver and gold ores in the mountains. The Alicantos that eat gold shine like the sun at night, and the ones that eat silver glow like the full moon. Prospectors follow these lights through the darkness, hoping to be led to rich veins of ore, but they generally just fall over a cliff.

Boobrie

An enormous, web-footed water bird said to haunt salt wells and lochs of Argyllshire in the Scottish Highlands, where it will catch and devour any beast or human venturing too close to the water’s edge.

Broxa

A bird from Eastern European Jewish folklore, believed to suck the milk from goats during the night. In the Middle Ages, however, it was claimed that these creatures had developed a taste for blood, similar to vampire bats.

Caladrius (or Charadrius, Caladre)

A miraculous white river-bird of medieval European folklore, with the ability to diagnose whether a patient will live or die. If the bird refuses to look at the patient, his or her death is sure to follow. It draws out illness—especially jaundice—from a sick person into itself, turning its feathers grey. Then it flies out into the sun, where the poison melts away, restoring the bird’s pure white plumage. Discovered in Persia by Alexander the Great, its dung cures cataracts in the eyes.

Gagana

A miraculous bird of Russian folklore, with copper claws and an iron beak. Often invoked in spells and incantations, it is said to live on the wondrous otherworldly Booyan Island, which is located in the Eastern Ocean near Paradise.

Halcyon (also Alcyone or Altion)

A Mediterranean seabird that is said to lay its eggs on the beach sand in midwinter, at the highest tide and amid the fiercest storms. Thereupon, the weather immediately calms for seven “brooding days” up to the chicks’ hatching on Winter Solstice, followed by seven “feeding days.” These 14 days of midwinter calm are therefore called by sailors “Halcyon days.” The sacred day of the Halcyon is December 15, beginning the Halcyon Days festival, a time of tranquility. This bird is equated with the Belted Kingfisher (Ceryle alcyon).

Hraesvelg (“Corpse-Eater” or Windmaker)

A vast, eagle-like bird of Norse mythology that nests upon the icy peaks of the frozen north. Her eaglets are the frigid winds blasted forth by the flapping of her mighty wings.

Strix (Greek, “Owl”; or Striga; pl. Striges)

A vampiric night bird of Roman legend that feeds on human flesh and blood. Various myths tell of people being transformed into these dreaded creatures. Pliny, in his Natural History (77 CE), writes that its name was once used as a curse, but beyond that he can only aver that the tales of them nursing their young must be false, as no bird except the bat suckles its young. Although they may have been bats originally, they have since been completely identified with owls, such that the genus Strix is assigned to these nocturnal birds.

Roc (Persian, Rukh; also Rucke)

A gigantic bird of Madagascar, famed from the journals of Marco Polo and the Arabian Nights stories of Sinbad, and said to be large enough to carry off elephants. It is described as resembling an immense eagle or vulture, but in reality, this was the enormous, flightless “Elephant Bird,” or Vouron Patra (Aepyornis maximus) (shown), which reached 11 feet in height and weighed 1,100 pounds. Its eggs were 3 feet in circumference, and had a liquid capacity of 2.35 gallons. These were the largest to have ever existed on Earth. This awesome avian was exterminated by humans in the 16th century. Because Vourons had insignificant wings and down-like pilli rather than true feathers, they were thought to be only the chicks of truly colossal flying adults. In two of the four Arabian Nights stories featuring the Roc, it retaliates for the killing of its chick by dropping boulders on ships. Gigantic “feathers” said to be from the Roc were actually dried fronds of the Raffia Palm (Raphia), which reach an impressive 80 feet in length. And Peter Costello suggests that the huge Wandering Albatross (Diomeda exultans), with wingspans up to 17.5 feet, could have also contributed to the legend of the Roc.

Shang Yung (or Shang Yang, Rainbird)

A fabulous one-legged bird that can change its height. It heralds the return of the rainy season and warns of floods. It draws water into its beak from rivers and seas, and blows it out in the form of rain onto the thirsty land; therefore, it is often petitioned in time of drought. Chinese children hop about hunched over on one foot, chanting, “It will thunder, it will rain, ‘cause the Shang Yang’s here again!”

Stymphalids (or Stymphalian Birds)

Similar to cranes in size and general shape, these are man-eating birds with brass beaks, claws, and feathers which they can shoot from their wings like arrows.

Named for the marshes of Stymphalia (Lake Stymphalos) in Arcadia, Greece, where they live, they terrorize the neighboring countryside until they are driven off and many killed by Heracles in his 6th Labor. The surviving birds settle on the island of Ares in the Euxine (Black) Sea, where Jason and the Argonauts later encounter them on their Quest of the Golden Fleece.

Tragopan (pl. Tragopomones)

According to Pliny, a horned bird endemic to Ethiopia. Medieval bestiaries describe it as a huge brown bird with two enormous ram’s horns on its purple head.

*Read more in the book.

The Element Encyclopedia of Magical Creatures by John & Caitlín Matthews

ADAR LLWCH GWIN

According to Celtic tradition, the Adar Llwch Gwin were giant birds, similar in kind to the Griffin, which were given to a warrior named Drudwas ap Tryffin by his fairy wife. The name derives from the Welsh words llwch (‘dust’) and gwin (‘wine’). The birds were said to understand human speech and to obey whatever command was given to them by their master. However, on one occasion, when Drudwas was about to do battle with the hero Arthur, he commanded them to kill the first man to enter the battle. Arthur himself was delayed and the birds immediately turned on Drudwas and tore him to pieces. Later, in medieval Welsh Poetry, the phrase ‘Adar Llwch Gwin’ came to describe hawks, falcons or brave men.

ALICANTO

This creature from the folklore of Chile emerges at night, shedding a golden or silvery light from its great wings. The Alicanto is a strange bird-like monster which likes to eat gold and silver, and if it discovers a rich vein of ore, will continue to eat until it is too heavy to fly. Gold prospectors in the Chilean foothills are always on the lookout for the Alicanto in the hope that it will lead them to golden riches. The wily bird, however, leads them only to their deaths, flashing its wings enticingly until they fall into a bottomless ravine.

BAR YACHRE

In ancient Jewish myth, Bar Yachre took the form of a giant eagle-like bird. In a similar fashion to the Roc, it consumed herds of cattle and sometimes human beings.

BARNACLE GOOSE

The Barnacle goose that migrates from the Arctic down into southern regions of Europe was a great mystery to medieval people. Throughout Europe, there arose many stories and explanations of where it could have come from when the colder weather brought it south. The most common legend relates that the bird was hatched from pieces of driftwood on which barnacles clustered. These barnacles were believed to be eggs from which they hatched. Another story says that they should really be called Tree Geese, because they hatch from trees that grow near the sea. As the fruit-like growths hang heavily, so the goose swims away into the sea. If they fall upon land, then they die.

BMOLA

Among the Western Abanaki peoples of north-east America, the Bmola was called the Wind Bird, a great bird whose coming heralded the freezing winds of the north.

COTZBALAM

In Mayan mythology, Cotzbalam was one of the four great birds who attacked the wooden bodies that were intended to become the first living humans. They each attacked a different part of the body to prevent the pollution of the primordial world. The others were Camazotz, Tecumbalam and Gucumatz.

CUCKOO

The first calling of the cuckoo announces spring and early summer to Europe, where it acts as a signal to sow crops. In Hindu tradition, the cuckoo is eternally wise, a bird who knows the past, present and future. In Japan, the cuckoo is a sign of unrequited love, possibly because of its continuous cuckooing. In Finland, the 18th May is St Eric’s day when St Eric is supposed to arrive with the migratory birds. He carries a cuckoo under one arm and a swallow in his hand. This was the traditional sign that the sowing of oats must be completed and the barley sowing begun. In medieval scholastic tradition, students calling ‘cuckoo’ was the signal that the scholastic term had begun, much to the disgust of the citizens of colle-giate towns, who would have to put up with yet more wild student behaviour. In medieval English folklore, the adult cuckoo’s habit of laying its eggs in the nests of other birds made it the symbol of a cuckold.

EMU

In the traditions of the Australian Aborigines, the emu is a totem bird and an ancestor. Emu is seen as one of the first creatures that rose with the sun from the sacred ocean. Objects sacred to tribes, such as the Chirunga and the Tjuringa, are often carved with the footprints of the bird. At certain times of year, elaborate ceremonies are performed in honour of Emu.

OWL

In the ancient world, the owl was associated not only with wisdom but also with darkness and death. It was sacred to the goddesses Athena and Demeter, and in most places its hooting presaged death or misfortune. In ancient Chinese mythology, the owl was a one-footed dancer with a human face who had originally been in the form of a drum. The raven-nosed emperor Yu forced Owl to perform a dance of submission for opposing him and made the owl the emblem of smiths. To this day the owl is not afraid of thunder because it was his dance that invented thunder and lightening.

In the lore of the Ainu people of Japan, the owl is generally considered to be evil and to bring misfortune. However, the eagle owl is trusted as it warns people of approaching evil. Such owls were kept in cages and venerated, though they were eventually sacrificed so that their spirits would take messages to the gods. The screech owl was said to warn against danger and to confer success in hunting, but the horned owl was a carrier of ill omen. It is considered unfortunate to have an owl fly in front of one, but total disaster to see it fly across the face of the moon. In the first instance, evil consequences could be avoided by spitting, but in the second the situation is so serious that the only remedy is to change one’s name and leave town!

According to the Cree people of North America, the presence of owls can make speaking very difficult. Owls are believed to cause stuttering and that, in turn, causes the owls much mirth. If someone stutters inadvertently, this is said to attract owls. However, if any of the Cree believe owls to be causing supernatural difficulties in the village, someone will go and purposely begin to stutter in the woods. This will summon an owl that can then be confronted with the problem and made to resolve it. Among the Aboriginal peoples of Arnhem Land, Australia, it was the owl that taught the correct song to sing at funeral rites. The song made the snake spirits dance in a lascivious way, which caused the owl to sing such a plaintive melody that they all slowed down and began a dignified dance that now heralds funerals.

Throughout much of Africa, the owl is considered to bring bad luck. In East Africa, to hear its hooting at night can be disastrous for a newborn baby. If the child already suffers from an illness, people say in Swahili that this child has been hooted over. In Ghana, it is believed that witches have owls as familiars or can change themselves into the shape of these birds. In this form, they enter people’s houses at night and attack their victims on the astral plane. The Yoruba of Nigeria relate that witches or sorcerers can leave their bodies at night, and that when they do so they take on the shape of owls. In daytime, they sit dozing harmlessly in the shade, but at night they enter their victims’ houses through a hole in the roof and suck their blood.

Traditionally a bird of ill omen, the owl is strongly associated with a figure from Welsh tradition known as Blodeuwedd. She is a woman created from flowers by the enchanters Math and Gwydion for their nephew Llew. Her name, which means ‘flower-face’, seems to have foreseen her destiny, which was to be turned into an owl as a punishment for her betrayal and connivance in the death of her husband. In The Mabinogion story of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ one of the significant animal helpers is the Owl of Cwm Cawlwyd, who along with his fellows is of great age and wisdom. Elsewhere, in Gaelic tradition, an early Scottish song, ‘Oran na Comhachaig’ preserves the following dialogue:

Oh wailing owl of Srona,

Mournful is thy bed this night,

If thou hast lived in the days of Donegal,

No wonder thy spirit is heavy.

I am coeval with the ancient oak,

Whose roots spread wide in yonder moss,

Many a race has past before me,

And still I am the lonely owl of Srona.

Once again, the owl is extremely ancient and has seen many ages pass. Yet its lot is a lonely one, ostracized as it is by other birds.

PHENG

In Japanese legend, the Pheng is a bird so large it can swallow a camel in one gulp. When its feathers fall to earth, humans can make water barrels from the quills. Like the Roc of Arabian legend, its wingspan blots out the sun when it is in flight.

ROC

The Roc (or Rukh) is the great bird of Middle Eastern legend. It looks like an eagle or vulture, with horns upon its head and a wingspan of astounding width. It can pick up and carry an elephant if it pleases. Marco Polo stated that he had seen one of its great feathers while at the court of Kublai Khan. He also reported that a Roc had carried off a bride. In The Thousand and One Nights tales of Arabia, the sailor Sinbad is shipwrecked on an island entirely made of brushwood enclosing a dome. It isn’t until the sky grows dark above him that he realizes that the whole island is a nest and that the dome is an egg. He clings to the talon of the Roc and drops from its grasp without the bird noticing. It is thought that the giant Aepyornis of Madagascar, which was 8-9 ft high and laid 13-in eggs was believed to have been the basis for many stories about the Roc. The Roc resembles tales told of the Simurgh and the Garuda.

SUN BIRDS

In the legends of Zimbabwe, the Sun Birds are golden birds, statues of which were found in the excavations of the city of Great Zimbabwe. These birds are in fact swallows whose swift flight is praised in Bantu tradition, where storytellers relate how the Sun Birds fly better than even the eagle. Among the Shona, the Sun Birds originally belonged to the great goddess, Dzivaguru. According to legend, the first man and woman lived in darkness because the sun had not yet been found. The god Nosenga caught the Sun Birds in his trap and from then on the sun shone upon the Earth.

WREN

The diminutive wren is the possessor of a wealth of lore concerning its abilities and it is the main player in an ancient ceremony that is still enacted in Celtic countries. The primary folk story of the wren, found across Europe, concerns a conference of birds who assemble to discover who shall be their king. The post will be awarded to the bird who flies the highest. All the birds in the contest take to the skies, each attempting to outfly the other until only the eagle is left in the race. Having outdistanced every other bird, the eagle begins to proclaim itself the king of the birds when the wren, who has been concealed in the eagle’s feathers on his back, pulls himself to his full height and chirps, ‘Behold your king!’ Some trace the roots of this story back to Sumerian mythology. The Greeks call the wren Basiliskos (‘little king’), while in Latin it is Regulus (‘king’); in Welsh it is Dryw (‘druid’) or Bren (‘king’) – from which the word ‘wren’ is derived – and in Manx and Irish Gaelic it is still remembered as Drui-en (‘the druid bird’).

Up until the 19th and early 20th centuries, the custom of Hunting the Wren was found in Ireland, Wales and Brittany. This custom took place on St Stephen’s Day, 26 December, when groups of boys and men went out with sticks to hunt and kill a wren, finally placing it in a ‘wren house’, a beribboned and decorated box, in which it is borne through the streets accompanied with songs. Some wren processions involved knocking on doors and asking for money, other involved the sale of a single wren feather to be placed in one’s hat. Finally, the wren was buried with reverence. This custom is of great antiquity, relating back to the turning of the year and the fact that the wren’s native name is associated with the druids who saw the wren as a bird of omen. It is evident that the druids saw the wren as the symbol of the old year and that its ritualized death and funeral procession was a necessary ceremonial to lay the old year to rest.

Whether this custom was associated with the ritual combat between the ruler of one cycle and another and was once a human combat that has became a substitute sacrifice, we shall never know. What remains is a body of lore and songs that lead us to believe the wren is dethroned in order to allow a new year to come in and grow strong. The Wren Boys still process about some villages on St Stephen’s Day in Ireland, although an actual wren is no longer killed these days. But in case it is thought that the wren was constantly subject to such barbarity in the past, it should be noted that to kill or injure a wren, its nest or eggs was considered to be a heinous crime throughout Britain and Ireland, except for the one wren killed at midwinter.

*Read more in the book.

Further Reading:

- Adar Rhiannon

- Birds of Rhiannon

- Welsh Celtic Lore: The Adar Rhiannon – The Singing Birds of Rhiannon

- Hell-hounds, Hyter Sprites, and god-fearing Mermaids

- Fae Folklore

- Mythical & Folklore Names

- Sunbird

- Barnacle goose myth

- Barnacle Goose: The Bird That Was Believed to Grow on Trees

- Medieval Lore: The Curious Myth of the Origin Barnacle Geese

- Barnacle Goose

- Pamola

- The Wren – King of Birds

- Tragopan

- Strix (mythology)

- STRIX : THE BAD OMEN

- Boobrie

- Folklore Thursday: The Boobrie

- Five Mythical Birds from Around the World

- Alicanto

- White Merle

Folklore in a Nutshell by Ronel

The raven, falcon, owl, wren, and domestic fowl hold special place in the memories of humankind. Some have helped with the hunt, while others have brought wisdom and prosperity. Tales such as the Goose who lay the Golden Eggs is one such lasting memory.

Other birds, though, are truly fantastical and aren’t found in modern times.

The three birds of Rhiannon who could sing the dead back to life haven’t been seen in centuries.

The boobrie that haunts the lochs of the Scottish Highlands, luring cattle and sheep from ships by imitating the sounds of their young before gobbling them up, hasn’t shown itself in ages.

Nemglan, the Irish king of fairy birds, hasn’t been spoken of since his son became king of Tara.

The White Merle, a bird whose song could restore sight, hasn’t been found since ancient Basque lore.

The hyter sprite, though, has made itself known from time-to-time by shape-shifting into sand martins and attacking people in flocks.

The Alicanto from Chile has had a marvellous time leading the greedy astray, while keeping gold ores for itself for its dinner.

And the Strix that closely resembles owls have had a feast of human flesh and blood whenever it can come across it without too much difficulty.

Though most birds seem to be fine companions, not all are okay with being captured or eaten, and have shown it by playing tricks or even eating humans and their domesticated animals. Personally, I’m okay with Galahad the peacock who has moved in with my chickens from his own accord to go where he wishes – I certainly don’t want to be kicked for arrogantly believing he belongs to me.

Birds of Faerie in Modern Culture

Guardians of Ga’Hoole book series by Kathryn Lasky

Strix Struma was a female Spotted Owl, or Strix occidentalis, and the dignified navigation ryb at the Great Ga’Hoole Tree. Part of the prestigious and respected Strix bloodline, she was greatly respected among both the young students at the Great Ga’Hoole Tree, particularly Otulissa, and the other rybs. She was a gracious and dignified flier. She also taught and coined the term “the Eyes of Glaumora” in reference to the stars.

Learn more here.

The Lord of the Rings (Middle-Earth) by JRR Tolkien

The Eagles were birds that served as messengers of Manwë. Among those were the Great Eagles, immense birds who were sentient, capable of speech, and often helped Men, Elves and Wizards in their quests to defeat evil. They were “devised” by Manwë Súlimo, King of the Valar, and were often called the Eagles of Manwë.

Learn more here.

Harry Potter books/films

“Owls are magical creatures most often used for delivering post and parcels in the wizarding world. They are known for their speed and discretion and can find recipients without an address.“— Description[src]

Owls are birds of prey. They belong to the order of Strigiformes and there are at least 200 species. They normally feed on small mammals, insects, and other birds. They do not make nests, instead sheltering inside trees, ground burrows, caves, and barns, or using other birds’ old nests.[7]

Normally, most British owls are nocturnal, and owls generally keep to themselves, but in the wizarding world they served many needed functions and had many sorts of personalities. Owls also appeared to understand magical people speaking English and could communicate with wizards and witches.[2][6]

Learn more here.

Disney’s Aladdin

“I love the way your foul little mind works!”—Jafar to Iago

Iago is the secondary antagonist in Disney’s 1992 animated feature film, Aladdin. He is a sarcastic, loud-mouthed parrot that served as Jafar‘s henchman during the latter’s attempt to rule Agrabah. Iago’s primary obsessions are riches and fame, which—coupled with his disdain for the Sultan‘s crackers—motivated his villainous deeds.

Learn more here.

Grimm TV series

Seltenvogel

A Seltenvogel (ZEL-tən-voh-gəl; Ger. selten “rare” + Vogel “bird”) is a rare bird-like Wesen. Seltenvogels are so rare in the Wesen community that they were thought to be extinct in most circles, although one appeared in “The Thing with Feathers“.

When woged, they have a multi-colored head and beak, and they gain glittering golden eyes. They are not very strong, given their long history of captivity, and easy prey for stronger Wesen. They are prized for developing a brittle, egg-shaped stone made mostly of gold, called an Unbezahlbar, and were enslaved or imprisoned in earlier times and force-fed to produce them. The stone develops in a sac in the Seltenvogel’s throat, and if it is not removed, the Seltenvogel can suffocate and die. It can be safely removed by making an incision vertically along the stone’s widest point, taking care to avoid the major blood-vessels of the throat, detaching it from the Faserig (Ger. “fibrous”) membrane containing it, and gently lifting the Unbezahlbar out.

Learn more here.

Steinadler

A Steinadler (STINE-ad-lur; Ger. “golden eagle”, lit. “stone eagle”) is a hawk-like Wesen that first appeared in “Three Coins in a Fuchsbau“.

When woged, Steinadlers gain a muzzle-like face and a beak-like nose. They have sparse, feather-like hair all over their body. They retain their human hair color. Their eyes are an extremely pale yellowish-green color. Like a few Wesen, they can localize their woge in their eyes without altering the rest of their body.

Steinadlers are renowned for their exceptional vision. Their superior vision is a result of having five times more visual sensory cells per millimeter of the retina than humans. They also have special colored oils in their eyes that reflect certain wavelengths of light. These special ocular biological factors endow them with near perfect night vision and a whole host of other ocular abilities.

Steinadlers are incredibly fast creatures, appearing as a blur when they run. They are stronger than humans and have superhuman reflexes.

Learn more here.

Raub-Kondor

A Raub-Kondor (ROWB-kohn-dorr; Ger. Raub “robbery” + Kondor “condor”) is a condor-like Wesen that appeared in “Endangered“. They are known to be one of the most dangerous hunters in the entire Wesen community.

When woged, Raub-Kondors grow black, feather-like hair all over their bodies except on their faces, which are dark tan in color. Their noses curve into a beak, and sharp talons sprout from their fingers. The most noticeable feature of a Raub-Kondor is their piercing, glowing, steel blue eyes. Like some other species of Wesen, Raub-Kondors have the ability to concentrate their woge to just their eyes.

They have amazing night vision when woged comparable to that of Steinadlers. Further augmenting their night vision is their telescopic vision, which allows them to see great distances. Raub-Kondors are capable of turning their heads up to 270 degrees in any direction. By exiting the woge, they can complete a full 360, as the neck twists the opposite direction if it is at the 270 degree mark. Raub-Kondors also possess an enhanced sense of smell and use this in their tracking.

Raub-Kondors are stronger than humans, as one was able to temporarily wrestle with a Blutbad, although he only won because he knocked him out with a wooden board. They also appear to be somewhat more durable, as one was still conscious and able to take on his attacker, then limp away after being smashed through a wooden wall.

Learn more here.

Birds of Faerie in My Writing

Origin of the Fae: Birds of Faerie

There are several birds from Faerie that have made their way into the mortal realm.

More than once goose with the ability to lay golden eggs have been captured by ignorant mortals. Most of them had been retrieved by the protectors of Faerie and taken to fae sanctuaries.

The Strix, lovers of blood and meat, have found their way into the forests of the mortal realm and have feasted on unwary mortals since before the Rift. Most owls ignore them completely for their taste for human flesh.

Known to the Scottish as the boobrie, a certain shape-shifting bird has developed a taste for cattle and sheep, though it prefers otters – if only Selkies weren’t wont to turn into these creatures and smite them for their tastes.

The birds of Rhiannon have changed shape and have taken refuge as pet birds across the globe in the form of budgies. They rarely use their powers anymore, though those who keep them do have better health than those without pet birds.

The White Merle had returned to Faerie after its abuse at mortal hands.

Nemglan was taken back to Faerie in disgrace after falling in love with a mortal woman and begetting a son.

Only the hyter sprites and Alicanto have been active as described in folklore without end.

What do you think of these birds of Faerie? Where did you hear about these birds for the first time? Any folklore about birds you’d like to share? Check out my Pinterest board dedicated to the subject.

You can now support my time in producing folklore posts (researching, writing and everything else involved) by buying me a coffee. This can be a once-off thing, or you can buy me coffee again in the future at your discretion.

*If you have difficulty commenting, check that you’ve ticked the data use block beneath the comment before leaving your comment. (Protecting your privacy per regulations.)

Want a taste of my writing? Sign up to my newsletter and get your free copy of Unseen, Faery Tales #2.

No-one writes about the fae like Ronel Janse van Vuuren.

Such a lot of reading! I enjoyed the first story about The Bird Grip very much although I was annoyed that the prince refused to listen to the fox’s warnings.

I know, right? Some people just won’t listen…

First, I applaud you on the amount of reading you must do in order to share here. The Bird Grip faerie tales moral and happy ending was a new read for me…enjoyed it. The ‘Modern Culture Birds’ stories are more familiar…Lord of the Rings and others. Another in depth and detailed AtoZ post.

CollectInTexasGal

Thanks, Sue. It does take a while, but there’s so much to learn!

So often there seems to be a picture of an Owl perched on a branch. I was amazed when I saw one in the wild close up. So much larger and the wing span was so impressive! Zulu Delta

They are amazing. One even hunted one of my dogs when I just moved out to the countryside — it was huge and it tried to steal my Rottweiler!

A lot of this was new to me. Your posts are so detailed and informative. Thank you for putting this together and all the hard work you did.

Thanks, Chrys 🙂 I enjoy doing folklore posts.

G’day Ronel,

So much research in putting together this post. I decided to check out some aboriginal stories relating to birds here in Australia. The main birds mentioned were magpies, brolga, crow (raven), emu, eagle and wrens. Then I found this PDF about birds mentioned in Aboriginal dreaming stories. http://eprints.batchelor.edu.au/id/eprint/141/1/Tideman_&_Whiteside_2010.pdf

That’s awesome! Thanks for sharing 🙂

Thank you for visiting my A to Z blog. So much research here to unpack! My husband is a birder and I try to me. I’ve loved being around birds all my life, and there have to be many through the ages who observed and wrote about birds – so many stories!

Birds are awesome to keep around 🙂

Loved a look at these faerie birds… while I knew a few of them from the stories I have read, there are so many I had no idea of until your post, and now am glad I read about them.. will definitely be reading through to the links as well slowly

My B post is here

Thanks, Vidya. I especially went looking for the lesser-known birds for this post 🙂

Wow, what a lot of bird lore! I look forward to seeing what else you find for us this month!

Thanks, Anne 🙂